Interviewer: Marvin Bendele

Location: Dziuk’s Meat Market – Castroville, TX

This interview was originally produced through a collaborative effort of the American Studies Department at the University of Texas at Austin, The Central Texas Barbecue Association, and The Southern Foodways Alliance.

Fieldwork coordinator: Dr. Elizabeth Engelhardt; Project consultant: Amy Evans

It is shared with Foodways Texas as part of a collaboration with the Southern Foodways Alliance to document food stories in Texas.

Originally from Poth, Texas, Marvin Dziuk moved to Castroville in 1974 at the age of eighteen to manage Dziuk’s Meat Market, the latest branch of the family business.

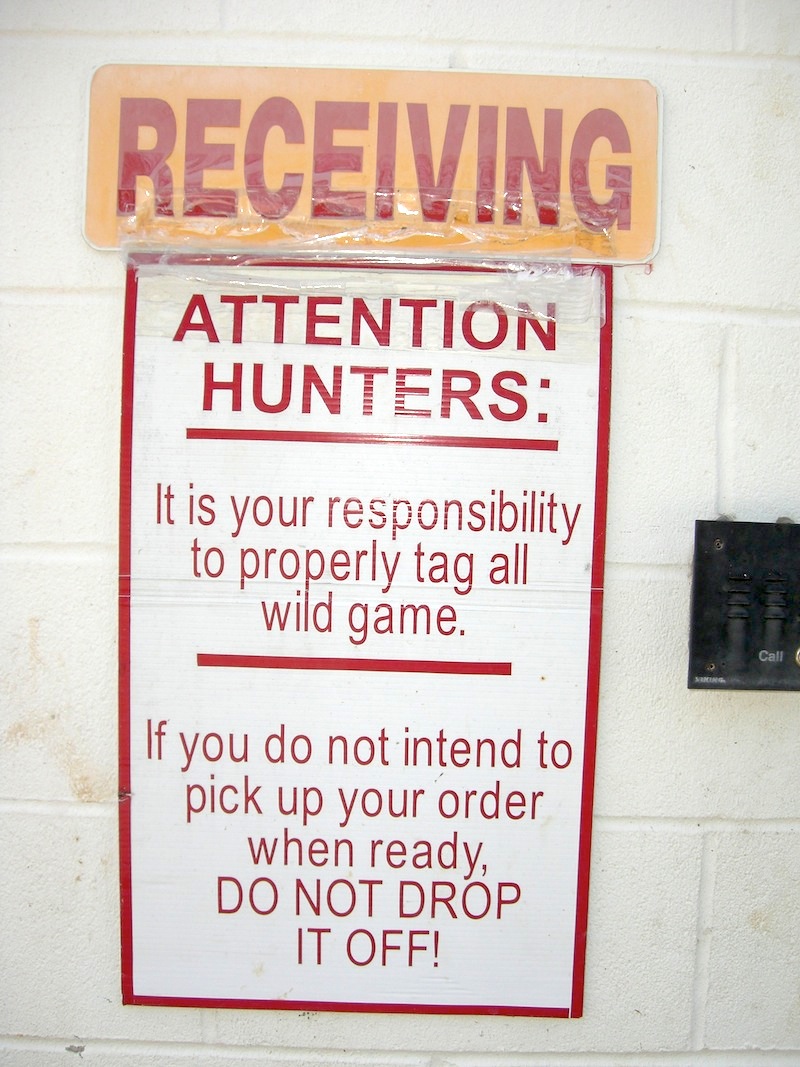

Dziuk’s Meat Market is known as one of the few establishments in Texas that makes and sells fresh Alsatian-style sausage, using ingredients from recipes that the pioneer families of Castroville brought with them when they arrived in Texas in the 1840s. The market is also a popular stop for deer hunters on their way to and from south and west Texas hunting leases.

Marvin Bendele: I’m here today with Mr. Marvin Dziuk at Dziuk’s Meat Market in Castroville, Texas. It’s about twenty miles west of San Antonio. OK Mr. Dziuk, I’d like to ask you to state your name and spell it, give your date of birth, and I’ll check the levels, make sure everything looks good.

Marvin Dziuk: Sure, Marvin Dziuk, that’s spelled M-a-r-v-i-n, last name is D-z-i-u-k, and date of birth is seven, five, fifty-six.

—

You said Alsatian-style and Polish-style. What’s the difference in the two different styles of sausage?

Well, basically the Alsatian sausage is a—I guess for someone that’s not from south Texas, the best way to describe an Alsatian sausage would be a kind of a brat. It’s a raw sausage that’s not—doesn’t have preservatives in it. So when you cook it, it’s going to be brown it’s not going to be red. It’s kind of like a raw brat, but the main ingredient that makes Alsatian sausage Alsatian is the coriander. That’s a product—it’s a spice that I have seen nowhere else—anywhere—that’s put coriander in sausage. They do in this unique—this area—and it’s very unique to this area and the people here think that it’s the greatest thing that ever happened, but after you get out of this immediate area, you’ll find that most people never heard of it and don’t care for it.

Well, I know—my experience with the Alsatian sausage, growing up in the area as well, is that it’s usually prepared—in my family, it was always prepared boiled. Do you know a lot of people that actually barbecue or grill it, and what do you usually do with it when you cook it?

Well, it can be done either way, to each his own. I mean, when you boil a sausage, to me you kind of—some of the flavor comes out into the water that you boil. And when you grill a sausage or barbecue it, it tends to hold all the flavor in, so it’s a lot richer finished product. It just totally changes the taste to where you can cook the sausage two different ways and you end up with two totally different products.

—

One product that I’ve had here is the dried sausage. And over the years, I’ve eaten it here and there, and I would admit that sometimes it tastes a little different than it does from year to year. Do you guys tweak the recipes, or is that just a function of the meat in that particular year or things like that?

Well, it’s really weird. I mean, we do a lot of deer processing to where there’s sometimes over a hundred, two hundred batches in a day put in the drying room, and for some reason, which I can’t totally explain, is everyone of those batches will have its own individual uniqueness to it. So it starts with, you know, how well the animal was field dressed after it was butchered. It goes back even further to probably what that animal was eating when he was butchered—what the muscle makeup was, because if you get into the feedlot business, you’ll learn that the more grain-fed an animal is, the different—the grain effects the taste of the meat. But we’re finding that even in sausages, and just all products, that it’s almost impossible to make a exact same product every time—especially dried sausage, where it’s a naturally fermented product, where it goes in a drying room for a few days. The—removing the water—it just doesn’t happen the same in every batch. It’s just really hard to put a finger on, but it’s—every batch has its own little uniqueness, but we do tweak a little bit but not much. After so many years, we’ve found that everyone’s taste buds are kind of unique in that everyone measures a sausage—what they eat from what they’re accustomed to eating. So, whatever you were raised on, you kind of grade everything else by that criteria. So, it doesn’t matter what you make—I always say it’s like an opinion: everybody has one, and you put ten people in the same room with the same product and you’re going to have ten different opinions. So, it’s basically the same way with sausage.

And does that—? I would think that in this area that probably is even a little bit more of the case, since a bunch of the people around here make their own sausage also. Do you think that’s probably one part of it?

Well yeah, most people don’t realize that there are, you know, that many different ways which you can do, but around here we’ve found that these people—every, everybody in this area has their own sausage recipe. And theirs is better than everybody else’s, and no one else’s is any good but theirs, because that’s what they’re used to eating. So, they grade everybody else’s by what they think it should taste like. So, it’s really an unfair test of anything—to amount to anything.

—

Well, can—in preparing the sausage, or getting it ready here, could you kind of just go through in—as detailed as you can, just the process of making your sausage? Without, of course, revealing any secrets, but—

Sure, well OK, the main thing that you have to have is you want a correct fat-to-lean ratio. You’ve got to have some fat in the meat because the flavor and the taste in meat is determined by the fat of the meat. In other words, if a meat has—you’ve—I’m sure everyone has had meat that is too lean. It has no flavor. That’s why filet mignon has to have bacon around it because it has no fat—it has no flavor. So, you have to find it somewhere—so, the flavor is in the fat. So, you have to have some fat, but you don’t want it too fat because then you have a problem with the amount of percent—of the bite. You don’t want it greasy, but you don’t want it dry, so you’ve got to have a real nice fat-lean ratio of meat. Some people like all pork, some—we make actually a pork and beef sausage. We put a little beef in it—it changes the product just a little bit. So, what you do is find a good, correct lean—probably about eighty-five percent lean product is what I like. I don’t like it any leaner than that because if you put it any leaner than eighty-five percent analytical lean, you have a product that in my opinion is kind of mealy and dry and kind of falls apart on you. Then, of course, you have to have the correct amount of salt because what salt does—it extracts the protein from the meat and that kind of binds the molecules, the fat molecules, and it extracts the protein and gives it the texture of sausage. And then after that, I mean, boy, then the whole can of worms opens. It’s salt—you’ve got the peppers and the cayennes and the jalapenos and the garlic and the cheeses and the coriander, and everything else you can find in the pantry goes in after that. But there again, it’s all personal preference, but the main thing in sausage is a good quality meat, salt, and some pepper, and after that—it’s personal preference after that. I mean, you can make a great product with salt and pepper and maybe a little garlic, and you have a wonderful product, and that’s really pretty close to what our Polish sausage is—is salt, pepper, garlic, and red pepper—just a real basic, won’t-come-back-and-haunt-you-type sausage. It’s just a great product, and that, of course, is—in this area, it’s all ground together, mixed together in a mechanical-type mixer. Then it’s stuffed into a pork casing—we use a natural pork casing to stuff the sausage in, and because—in this area, they don’t believe in preservatives, which the nitrate is the main preservative used in sausage, and that preservative is what makes the sausage—it’s why hams are red, it’s why bacon is red, that’s why all that is red. If you put preservatives in it, it’s red when it’s cooked. Our sausage is kind of a brown, roast appearance when it’s cooked, because it doesn’t have the nitrates in it. And because it doesn’t have nitrates in it, it doesn’t have a long shelf life. So, we like to make sausage and see it consumed in no more than two, three, four days at the most, to where the convenience stores and the grocery stores can’t basically have that type of sausage because they can’t get it through central distribution that quick. So, they’ve either got to freeze it or vacuum pack it or do something to try to extend the shelf life, because the natural product, we found, is just a totally unique product.

What is the process of stuffing? I know a lot of people that make it around here on their own, just mixing the venison and the pork, they have their—some of them have the crank stuffers. What do you guys use?

Well, basically what we use is, we have a water stuffer. It’s basically a piston-type machine that has a cylinder, and that cylinder is a piston and on one side of the piston is water and on the other side of the piston is the product, and then that water pressure actually pushes it through a stuffing horn into a casing. But there’s vacuum stuffers, there’s actually mechanical stuffers, gear driven. The water is just—use water pressure, that’s what we use, but there’s certainly great mechanical stuffers. And like I said, the best, newest thing out there is vacuum stuffers, and the product is actually stuffed under a vacuum, so those do give you a bit of a different texture—a bit of a different bite. But those are more for mass-production type—you know, we do every little batch separate. So, half of our batches wouldn’t be enough to even get anything out of the machine. So those are for continuous-type use.

In terms of smoking, do you smoke some of them longer than others? And what does that have to do with the flavor of it?

Actually, the reason for smoking is—there’s two reasons. One, they say that the smoke on the exterior is more of a preservative and it, also, of course, is for the smoke flavor. A lot of people say they like the smoke flavor, but that there again is personal preference. What you do is you try to smoke a sausage when it’s—when the sausage casing is still wet and impervious [sic], that’s when you apply the smoke. And then once the casing dries, the smoking process—smoke won’t penetrate anymore. It only—the smoke only penetrates the casing when the casing has a tacky feel to it. So, that’s when you apply your smoke. And then once the casing is dried, that is sealed. So, if you’re making a dry sausage, the main reason for smoking is for of course, shelf life and flavor—fresh sausage the same way, for flavor, because some people don’t always end up grilling it, but if you’re going to grill it anyway, it doesn’t matter if it’s smoked or not—you’re going to get all the smoke on it usually when you grill it. Unless you want a certain flavor of smoke like hickory or something, but there again the smoking is not necessary, and a lot of the Alsatian sausage is sold raw—not even smoked.

Does the—how long does it usually take to make the dry sausage? How long does it take to dry it? And I guess, of course, it depends on how big the sausages are. But also the jerky—how long does that—what’s the process and how long does that take?

You go to the dry sausage—I can make it, if I had to, in twenty-four hours. But what we prefer—we prefer a method of more of a natural, slower-type drying process that takes about five days, and what that does—we do it at a lot lower temperature, a high humidity, but a low temperature. And when we make a dry sausage in a day versus make it in five days, the end product is totally different. If everything is done the same except the drying process, by doing it in five makes it taste one way and the other way makes it taste like a totally different product. So, there again you’re supposed to take the internal temperature to 151 degrees to make sure it’s fully cooked, and we do do that, but some people don’t always heat treat their products. But we like to heat-treat them just for the consumer safety part of it. And there again it takes—you can change the process a dozen different ways and have a dozen different flavored products at the end. So, you just have to kind of find what you want to do and what works for you and your facility-wise and customer-wise and produce that product. And like the jerkys—we make a real thin product about an eighth of a—maybe eighth, maybe three-sixteenths product, where we actually slice it—slice the meat up. It’s temped out first so you can slice it, not frozen, not totally thawed, about half way in between—slice it and then let it thaw completely. And then we put it in the meat tumbler and add the ingredients and tumble it in there, and that actually massages it and mixes the seasoning, and we’ll put that in the smokehouse, and we’ll have it ready in four hours. You know, and then we have another thicker product that we actually marinate and let sit for forty-eight hours in the cooler. And then take it out and smoke it for a day, and then let it dry for two days. And it’s more of a, you know, one-inch-thick product. So, it’s two completely totally different products made out of the same type of meat, just a different process.